Well, I’ve finally visited the famous Gallipoli Peninsula. Lorna, David and I took a taxi to Sultanahmet early Saturday morning to meet the Feztour bus. No traffic at 6 A.M.! There were three others, all Aussies. You’ll see why.

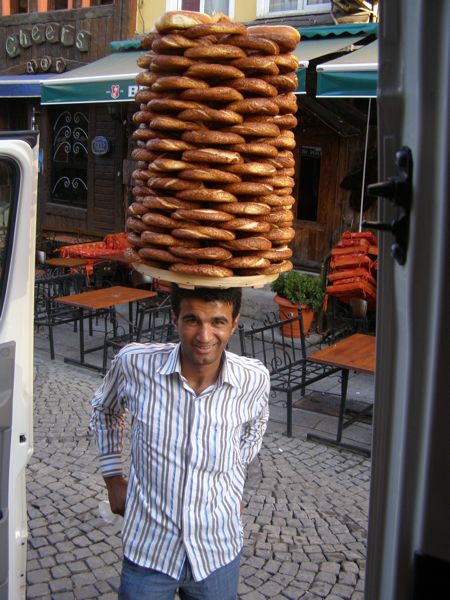

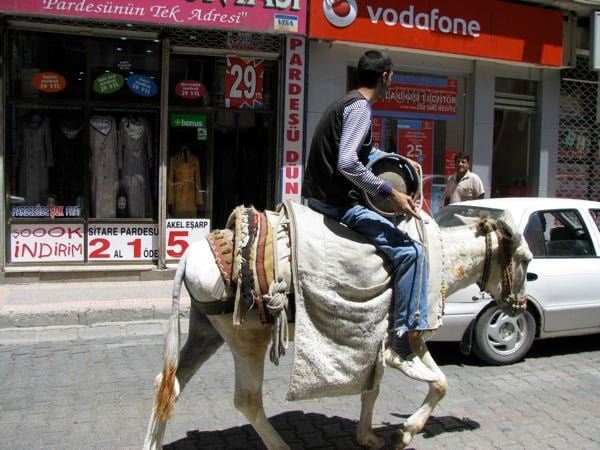

A simitçi stopped at our service bus offering a sesame-encrusted breakfast.

We happened on a Circumcision Procession in a small town. Happy boys—for now!

It was a gorgeous drive down the Peninsula, and after lunch we visited numerous museums, graveyards, and monuments as our tour guide, Perihan, filled us in on the details of the Gallipoli campaign. Here’s what I learned:

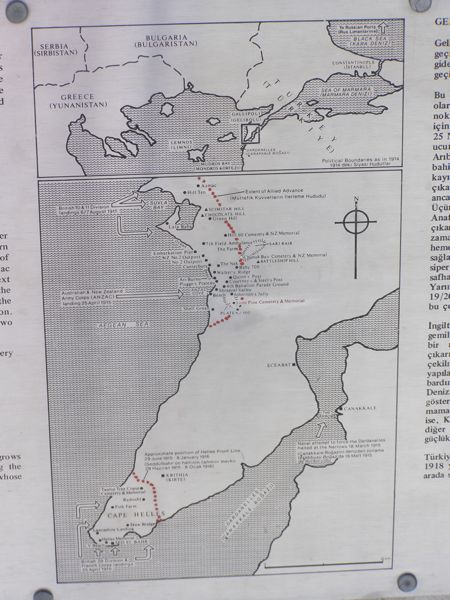

During World War I, the Allies wanted an ice-free sea route to Russia, and the only available option was through the Dardanelles Strait, which runs from the Aegean Sea to the Marmara, then the Bosphorus Strait connects the Marmara with the Black Sea—and Russia (as well as Romania and Bulgaria). It was all controlled by the Turks (the Ottoman Empire).

The Gallipoli Peninsula

After a thwarted naval attack in February, 1915, the Allies decided that they couldn’t take the Dardanelles with naval power alone, so they began strategizing to take control of the entire Gallipoli Peninsula, dominating the Ottoman land forces. The British took on the campaign, enlisting Australian and New Zealand troops that had been training in Egypt (ANZAC: Australian and New Zealand Army Corps).

A Turkish man pauses at a rough statue outside the museum.

Hence began a bloody 8 ½ months on the Gallipoli Peninsula. The first attacks were made on April 25th, 1915, with the major focus (five landings) on Hellespont, the tip of the peninsula. There was another strategic point where the allies intended to land, straight across the peninsula from the narrows of the strait, with an intent to overtake the high point of the Peninsula (Hill 971, or Chunuk Bair). Unfortunately, as the ships waited through the night to land, they drifted 1½ miles north of their goal. Instead of landing on a smooth beach with low, rolling terrain, they landed on a beach with a high ridge beyond. This one mistake may have cost them this campaign, not to mention the many thousands of lives that were lost on both sides. (Allies: 43,000, Turks: 87,000—That’s over 500 killed per day in hand-to-hand combat for 8 ½ months.)

In the end, the Allies reatreated, pulling out their last soldiers on January 9, 1916.

The most significant thing to the Turks was, of course, that they retained control over the Dardanelles, hence shipping routes to Russia and Eastern Europe.

Our guide Perihan at a cemetery near Anzac Cove

Another significant thing was a young military commander, Mustafa Kemal, who “saved the day” so to speak, and later became the first ruler of the Turkish Republic (8 years later). Because the Turkish general thought the ANZAC landing was merely a feint and that the major attack would occur at the north end of the peninsula, most of the Turkish forces were posted there, leaving only a few smaller battalions to defend the central peninsula. Mustafa Kemal was put in charge of these battalions, and when he realized that thousands of ANZAC soldiers were climbing the bluffs above the beach, he set up a line of defense up in the hills. He established a headquarters on the third ridge, now known as “Kemal’s Hill”.

A monument to Mustafa Kemal (Ataturk) on “Kemal’s Hill” where he was wounded in battle.

Kemal’s order to his men is renowned among Turks: “I do not expect you to attack, I order you to die! In the time which passes until we die, other troops and commanders can take your place!”

Me at the Anzac Cemetery—facing the Aegean Sea

A grave from the “horseless” Light Horse Brigade that stormed Anzac Cove—age 25

The fighting at Gallipoli lasted over 8 months, well into the winter.

Lone Pine Cemetery, atop the highest hill.

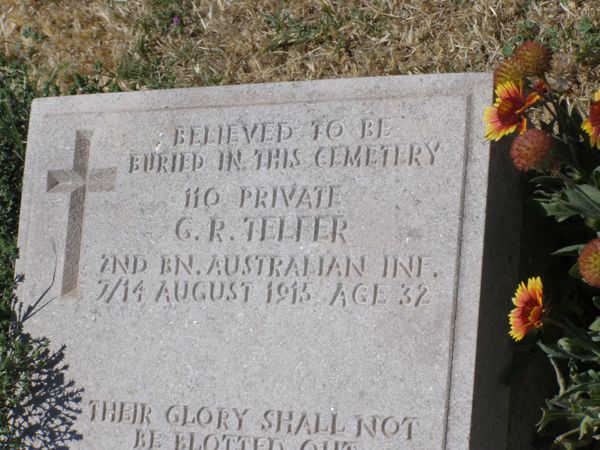

One of many “maybe” markers–“Believed to be buried…”

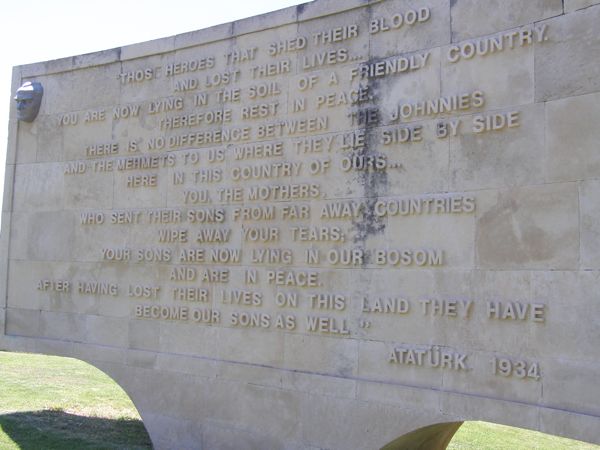

I was particularly moved by this message on a monument near the ANZAC seaside graveyard:

“THOSE HEROES THAT SHED THEIR BLOOD AND LOST THEIR LIVES…

YOU ARE NOW LYING IN THE SOIL OF A FRIENDLY COUNTRY. THEREFORE REST IN PEACE.

THERE IS NO DIFFERENCE BETWEEN THE JOHNNIES AND THE MEHMETS TO US WHERE THEY LIE SIDE BY SIDE HERE IN THIS COUNTRY OF OURS…

YOU, THE MOTHERS, WHO SENT THEIR SONS FROM FAR AWAY COUNTRIES WIPE AWAY YOUR TEARS; YOUR SONS ARE NOW LYING IN OUR BOSOM AND ARE IN PEACE.

AFTER HAVING LOST THEIR LIVES ON THIS LAND THEY HAVE BECOME OUR SONS AS WELL.”

~ATATÜRK 1934

This is a huge monument, a touching quote—note Ataturk’s head at the upper left.

There are numerous tales of kindness on both sides of the battle lines: soldiers tossing cigarettes, candy, and food across the narrow expanse between the trenches. There are stories of Johnnies (Allied forces) giving water to dying Mehmets (Turks), and Mehmets carrying wounded Johnnies back to the Allied trenches. It’s hard to imagine crouching in narrow, muddy trenches hour after hour, day after day, week after week, starved and waiting for imminent death. Many of the thousands of bodies were never identified, although many mass graves were unearthed to identify and send remains back to their homelands. Some regiments were completely wiped out.

Mehmet carries a wounded Johnny

Every year on Anzak Day (April 25th) many thousands (particularly Aussies and Kiwis) visit the Gallipoli Peninsula to pay homage to those who gave their lives.

If you’re interested in seeing a map of the area, here are two links, one to an Ottoman map (with Ottoman writing) and the other to a satellite photo of the region.

Ottoman map of the Gallipoli Peninsula

An aerial view of the Gallipoli Peninsula

A statue of the oldest living Turkish Gallipoli soldier, who died at age 110.

We finished touring around 5:00, then hopped a ferry over to Çanakkale, where a Trojan horse guards the harbor. It’s not the original, but a very cool one from the 2004 movie Troy, starring Brad Pitt.

Trojan Horse, Çanakkale

We stayed at a lovely resort hotel on the beach, where the cicadas put up quite a ruckus until the evening temperatures cooled.

A cicada that was sojourning on our balcony–imagine 10,000 of them singing at once. ARAUGHHH!!!!!

An evening henna party and another wedding party next door provided live music for our listening pleasure. Really.

David wonders about summer Ottoman wear displayed in our hotel lobby.

There was one downside to our tour, though. Unbeknownst to us, our tour didn’t include return transportation to Istanbul (no WONDER it was such a good deal). We learned on Saturday that we’d have to find our own way back, which was a shock. They offered to include us on a tour of Troy and drive us back to Istanbul (for $60), but the return was very late, and we’d still have to get ourselves back to campus. Sigh… Both Lorna and David were great sports, and the Metro bus was fine. They even have stewards who serve tea and snacks. It took us over 7 hours to get back to Istanbul, nearly two to cross the city, and yet another to get back to campus. Sigh…

Oh, well. I got to Gallipoli, learned a lot, and saw a Trojan horse. Not bad.