An English teacher on a biology trip? Go figure! I just returned from a school ecology trip to Dalyan, on Turkey’s Mediterranean coast. Lovely. More than lovely.

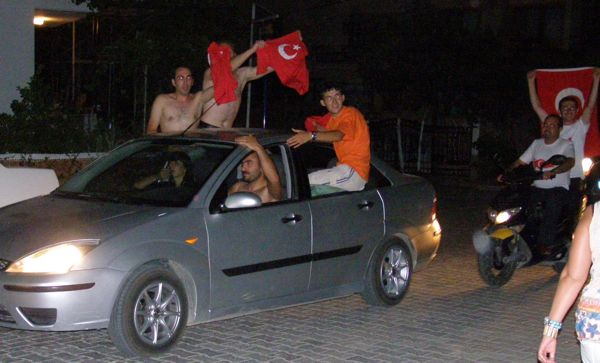

We arrived late, just in time to hear Turkey’s soccer team beat Croatia in overtime, winning a spot in the European Cup semi-finals. The streets immediately filled with celebrating fans honking, chanting, singing, and waving flags. The owner of the Metin Hotel found it a bit deli—crazy. We loved it.

Celebrating soccer fans in the streets of Dalyan

The first morning dawned bright—and hot. Temps were in the high 80’s and 90’s all four days (28 to 35 C.). Luckily, we were mostly in and on the water, the focus of this biology trip (the fourth annual) expertly organized by Gaby McDonald, a South African biology teacher at Robert College. Our eight students were joined by seven science teachers-in-training from Bilkent University (with supervisor Margaret Sands). The plan for the week included two days of hands-on biology activities with follow-up sessions, then two days of recreational adventures. We were also privileged with a night visit to the beach to see loggerhead turtles lay their eggs; the beaches are off-limits to anyone but researchers during the nesting season.

Gaby runs one of many information/feedback sessions on ecological studies.

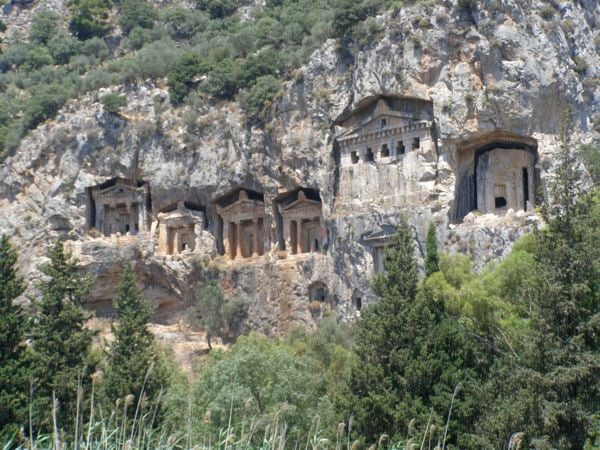

Back to the first day. After an introductory session by Gaby and her assistant, Noah Billig, we slathered ourselves with sunscreen and walked three blocks to the wharf. Students carried the two huge wooden crates filled with scientific gear. Captain Ramazan welcomed us to our boat/classroom, and we marveled at the ornate tombs carved into the marble cliffs across the waterway. Gorgeous!

Picturesque marble Lycian tombs dominate the veiw from Dalyan.

The day was devoted to water samplings, vegetation surveys, and river current measurements—a mammoth task, in my mind. We moored near a group of sheep clustered in the shade, and from there the work began. One team hopped into a small boat with a long rope to measure the width of the river, then measure the depth at 5 meter intervals as they rowed back from the far shore.

Captain Ramazan rows two girls across the river to measure width and depth.

Another group set up meter-sized quadrants to survey the vegetation along the shoreline (and in the water).

Investigating vegetation within randomly-placed quadrants.

Once those tasks were completed, we headed out to the middle, where water samples were taken at varying depths and analyzed on a number of scales to determine clarity, salinity, phosphate content, etc.

Scientific equipment aids water measurements.

Lastly, six students jumped into the river to help measure the current. The rope with meter measurements was stretched along behind the boat, and pairs of students were posted at 5-meter intervals. Another student dropped two oranges into the water while a second used a stopwatch to time the oranges’ progression along the rope. The process was far slower than expected, and one orange did little but circle below the boat. Our determination was that the wind was counteracting the current or there was little current. We’d discuss possible reasons for it later.

Students continue water samplings from the boat/classroom.

We repeated the water quality tests halfway down the river, where we also wolfed down our lunch of tomato, cucumber, cheese, and salami sandwiches. The Turkish bread is always fresh and crusty, and beyaz peynir (white cheese) is delicious—YUM!!!

Finally, we reached the Mediterranean, where we were set free for a few hours to enjoy the beach and the waves. The sea was much more refreshing than the river’s warm water. We did one final water test just inside the inlet, then motored home with many exhausted students fast asleep.

Tourists enjoying Dalyan beach

After returning home we showered, napped, and held a follow-up session to analyze our data. It was clear that water temperatures, phosphates, and turbidity levels (lack of clarity) were higher upstream, away from the sea. Of course, this also contributed to higher vegetation levels. Students discussed the importance of controlling pollution in the river to maximize the populations of aquatic animals that contribute to the ecosystem.

Pensive students (Squeak and Ayse) during a feedback session.

We then enjoyed the hotel’s scrumptious buffet (mezes, Turkish hors d’oeuvres, are my favorite, so I focused on those). Later we gathered at a local karaoke bar for Gaby’s powerpoint on sea turtles, a focus of much of our research. Loggerhead turtles are amazing. They can live up to 200 years (though the average is 30-60) and can weigh up to 350 pounds. They reach sexual maturity at about 30, and females nest every three years, laying up to 35 pounds of eggs, often in three separate nests. Loggerheads often migrate thousands of miles, although the females return to the beach of their birth to lay their eggs. Recent satellite transmitter data has shown that Turkey’s turtles migrate to Tunesia. It’s interesting, too, to note that loggerhead hatchlings increase their weight more than 6000 times from birth to adulthood. If we did that, we’d weigh about 42,000 pounds.

Crab bait awaits.

Sunday was crabbing day. Ramazan piloted the boat as he tied chicken skin and a heavy nut (hardware) onto lengths of fish line. Once we were anchored in a choice location, the eight lines were thrown into the water around the boat.

Within minutes, five students were reeling in blue crabs, which Ramazan expertly netted and brought to the surface.

Captain Ramazan beams after netting a blue crab.

Gaby taught us how to determine the sex (yup—it’s pretty easy), whether the females were in berry (with eggs), and how to measure the carapace (shell). After noting all the features of each crab, its shell was marked with fingernail polish and it was placed in a bucket, where the morning’s catch soon became a knot of inter-connected pincers and shells. After an hour and a half, a mere 14 crabs had been caught. Ramazan dumped them back in the river to burrow into the mud.

Students measure and mark blue crabs (Ayça and Lal)

We once again headed to the beach for lunch and a swim—ah, the refreshing Mediterranean! The beach, by the way, has rules against putting up sun umbrellas, as they might bore into a turtle nest. They have permanent wicker umbrellas with wooden beach chairs available, otherwise it’s full-sun exposure.

Dalyan beach’s “official” beach umbrellas and chairs

We returned to our crabbing spot to catch crabs again, though with disappointing results—only 4 crabs caught. One of the four was already marked, so using the ratio of pre-caught to repeatedly caught crabs, we computed the population of the 100 square meter area to be about 52 crabs, the same computation as the previous year, although they had caught 50 (compared to our measly 18.) Interesting. Our biggest concern was that none of the females were in berry. Why?

After we returned to the hotel, we had another session to evaluate the results, and groups of students proposed methods of preserving the crab population (the loggerheads’ favorite food).

A post-discussion group photo of young biologists

That night half of us left for the beach with Bekir Bey, a ministry official who Gaby has worked with over the years of this project. Under his escort, we were able to get past the gates onto the beach, where a team of researchers from Pamukkale University are studying loggerhead turtles. They scout the 3-kilometer beach every night, watching for turtles that come in to nest. It’s important to catch each turtle before she covers her nest, as she does an incredible job of throwing sand behind her and over the nest, making it difficult to determine where it is. Although loggerheads are easily frightened away as they search for a nesting spot, once they begin laying, they are in for the count. As they lay their eggs, researchers take measurements and either mark new turtles or snip a sample of tissue from the hind flipper of turtles that have already been marked. Once the turtle has returned to the sea, the researchers dig down about six inches toward the well-covered nest and lay a metal grid over the nest to protect it from fox or other predators. The grid is spaced wide enough to allow the hatchlings to wriggle through, though narrow enough to prevent animals from stealing the eggs. In 55 days the researchers will revisit the nest, then try to protect the hatchlings as they head toward the sea. Unhatched eggs are used for study. Did you know that a sea turtle’s sex is determined by the temperature of the egg’s environment? Let’s see…I think the females are the hotter ones… (29 degrees is the dividing line.)

Photo from Wikipedia: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Image:Loggerhead_close_up.jpg

The moon rose around midnight, charming the beach as we waited to see our turtle lay her eggs. She laid her eggs quickly, so researchers had to do measurements as she headed back to the sea. I wasn’t allowed to use a flash, but I got a few time exposures in the dark that showed the her silouhette as they worked with her.

Time exposures of our female loggerhead turtle being measured after leaving her nest

Our last two days were fun, fun, fun. Monday we went white-water rafting (a 3-hour drive, but WELL worth it.)

Rafting photos by Alternatif Outdoor Rafting

On the last day we went sea kayaking, a new adventure for most of us. I could have stayed out there all day, but we paddled for only a few hours, exploring one of the most picturesque coves of the area.

Too much information, I know—but it was WONDERFUL! I learned a lot about turtles, about ecological balance, and about traveling and adventuring with Turkish kids. I was once again reminded of Turkey’s varied and spectacular scenery.

Thank you, Gaby!